They fought together, rested and ate together and ultimately died together.

It is that time of year when we remember the fallen in wars, particularly those in the Great War. Last year, being the 100th. anniversary of the armistice, I was prompted to try and discover more about the role one of my grandfathers played in the war. His name was Edwin Clark and I was only four years old when he died so knew little about him. I soon discovered that he had a full on war in the Canadian Field Artillery and it came as a pleasant surprise to find that he had the dangerous job of a “driver” looking after and riding the war horses that pulled the guns.

I gathered so much information that I decided to write a book about his eventful personal war. But during my research I was so intrigued with the men’s obvious emotional relationship with their horses, the story became as much about the heroics and deprivations of the horses as the men.

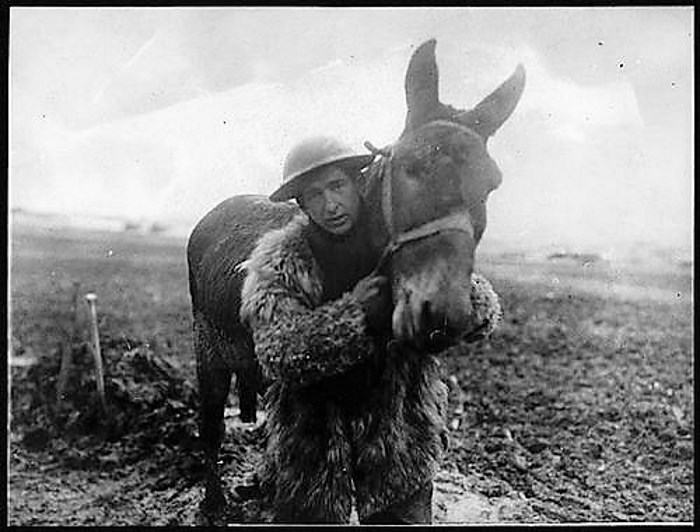

The men spent most of their waking hours caring for them often under almost impossible conditions. They fought together, rested and ate together, often slept together and ultimately died together. There is no getting away from the fact that their lives were unforgiving and unremitting, but at the same time the men responsible for them lavished as much care as they could to alleviate their suffering and formed incredible bonds with them.

The men were devoted to the war horses.

The horses and mules became friends, confidants, fellow comrades and pseudo counsellors with who the men could air their grievances, discuss their suffering and help alleviate their depression and melancholy. Without their companionship the physical and mental well-being of the men would have been worse than it was. The relationship is probably one of the ultimate examples of man’s dependence on animals for solace.

Their devotion to the horses is evident by how an officer responsible for censoring their letters home to mothers, wives and girlfriends stated:

“Drivers almost wept as they wrote of their faithful friends – the horses – wishing so much that they could be given more feed and better shelter. Such care and attention they gave these dumb animals. When nothing else was available an old sock was used to rub them down or to bandage a cracked heel while breast collar and girth were eased by wrapping light articles around the harness to keep it from rubbing the sore spot”.

Legitimate targets

The horses and mules were viewed as legitimate targets by both sides. They faced being shelled, bombed, gassed, sometimes shot and suffered horrific shrapnel injuries. Many suffered shell shock and remarkably others learned to lie down and take cover when under fire. Like most of the human recruits, the horses had never experienced such noise, chaos, smells, violence and hardships and they did not have the capacity to realise what was happening to them or likely to happen to them. So everything occurring around them was terrifying until they became accustomed to it.

There are no exact statistics on the average lifespan of a World War One horse arriving at the front, but for most of them it was very short. They died in large numbers daily and were replaced by new recruits. Very few managed to survive the whole war. The few that did manage to see it through to the end were shown no compassion and were just slaughtered for meat or sold to work on farms, being logistically too difficult and expensive to repatriate. Their suffering was immense and unlike the men, none of them returned home.

I find it rather poignant that when Edwin, my grandfather was severely wounded for the third time and invalided from the war, just four weeks before it ended, he was tending to the horses. He was giving them their nightly feed, water and grooming a mile behind the front line when an enemy plane flew over and dropped a bombs in the midst of them killing and wounding many drivers and horses. Edwin did thankfully make it back, but after three years continuous action in most of the major battles on the western front he returned both physically and mentally scarred. We owe them all so much.

Suitable for horse lovers and military hist0rians of all ages

Special offer direct from Publisher bitzabooks.com (bitzabooks@gamil.com) £11.00 incl. p&p. UK ORDERS ONLY

Buy from publisher Bitzabooks.com direct using PayPal secure.

Extract From Book

They docked at the port of Le Havre at dawn and disembarked in a heavy drizzle. Edwin and the other drivers were ordered to remove the horses from their cramped stalls. Unloading restless and frightened horses was a long, tedious and dangerous operation and once on dry land they had to be fed and watered. Then Edwin and his comrades had their breakfast. Edwin had arrived in France, safe and sound, four months after arriving in England, fully trained to meet the enemy at the western front. And meeting the enemy was going to come sooner than probably any of them expected as they were ordered to head straight for Belgium and the bitter fighting in the trenches.

They hooked up their teams and were given the order to “walk march” through the streets of Le Havre to a huge rest camp on the outskirts consisting of rows of huts and tents and field kitchens. It was noted in the WD that a very unlucky Sergeant Gailer was killed during the train journey when he fell out of an open door of a carriage – their first casualty of their war in France. They had lunch, groomed the horses and cleaned the harnesses, but had little chance to rest as they were on the move again and ordered to march to Le Havre railway station. Horses, guns, forage and equipment had to be loaded again with eight horses per freight car – 4 horses at each end with heads facing the centre and the men lounging between them. The guns were roped down and transported on flat carriages. They were on their way to the front in a hurry and I can only imagine how nervous Edwin must have been. They were to face an arduous train journey and long marches over several days to reach their destination in Belgium.