A lifeline for the city’s pets for 40 years.

London was a far different place in the 1930s in respect to the number of animals residing within the Greater London area and the standard of animal welfare. Estimates suggest that there were 1.5 million cats, 400,000 dogs, 18,000 horses and a multitude of livestock including pigs and sheep. Many Londoners still lived in real poverty, not the perceived poverty of today and most dogs and cats were left to wander the streets and mingle with the large number of strays. Disease was rife and many suffered injuries particularly in road accidents. Few veterinary surgeries had out of hours services and there were even fewer animal rescue organisations. There were no council animal wardens and the police and fire brigade had little interest, ability or equipment to deal with animal related incidents. So, there was an opening for a service to fill all these gaps.

So it was fortunate that in 1936 a new London emergency service quietly appeared on the scene which over the next four decades proved to be a lifeline to London’s sick, injured or trapped stray and wild animals and worried pet owners within a ten mile radius of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) headquarters at 105 Jermyn Street, Piccadilly.

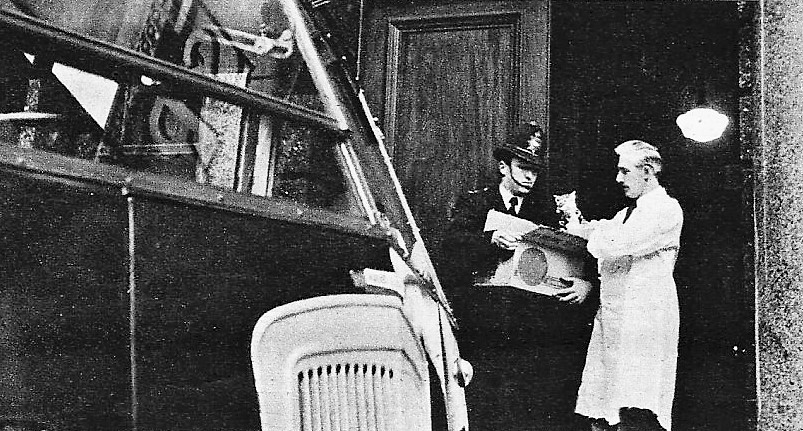

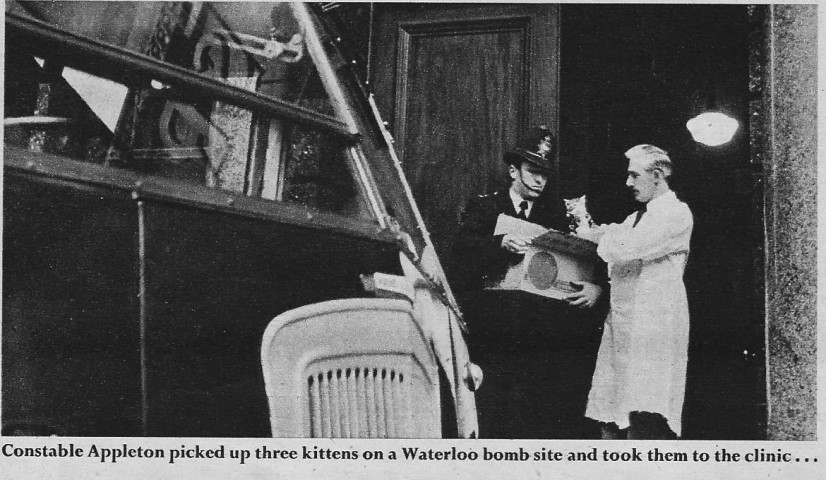

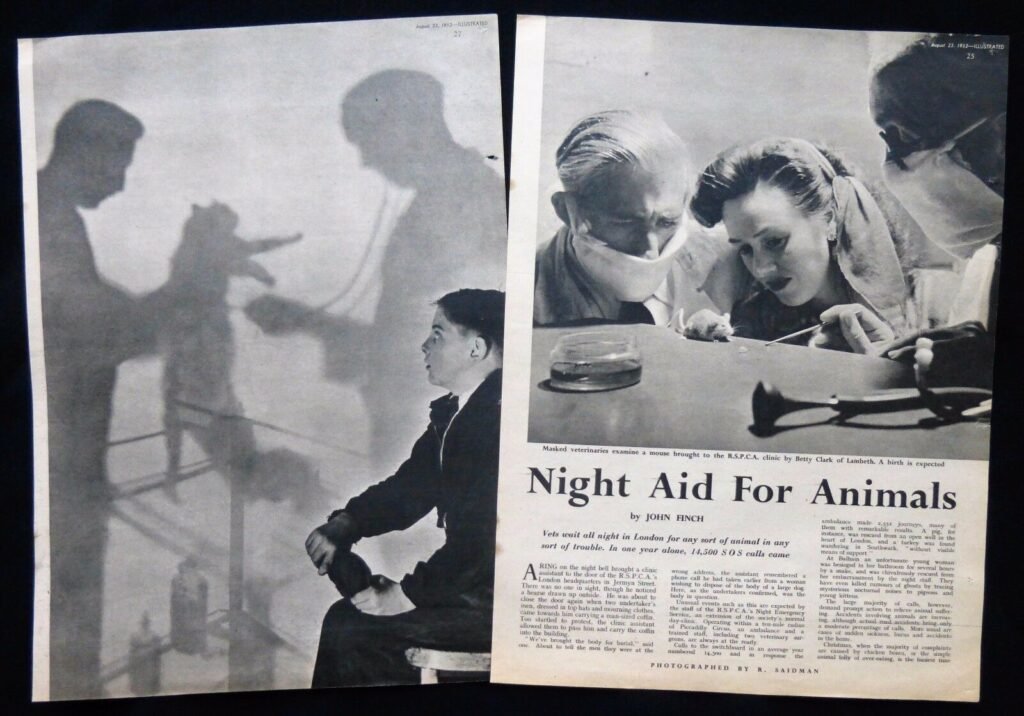

Its expertise and dedicated staff were in great demand by the London Fire Brigade, Metropolitan Police, London Underground, River & Transport Police and British Rail and any other agency that had a problem. Whether it was a dog or cat hit by a train or car, an animal struggling in the Thames or a cat stuck up a tree their rapid response vehicle, packed with specialist animal rescue equipment was always at the ready. It quickly became the true fourth emergency service in London at night and weekends. An emergency clinic operated every evening at 9 p.m. and a vet was always on call. In many respects it was ahead of its time, arguably the first combined out of hours veterinary and animal rescue service.

An auspicious start at Crystal Palace fire

Initially it was based in an RSPCA hospital in a converted house in Clarendon Drive, Putney, and was known just as the “Night Clinic” with a staff of one vet and a clinic assistant. This new emergency service got off to an auspicious start when at about 9 p.m. on the night of the 30th. November 1936 it attended the great Crystal Palace fire at the request of the London Fire Brigade. Working alongside 700 Police officers, 438 Firemen and 88 fire tenders, its staff of two and one van helped rescue and attend to animals involved in the fire. According to an RSPCA report of the incident they arrived:

“With an ambulance fully equipped for first aid treatment, reached the scene in record time, and earned the grateful thanks of both Fire Brigade and Police”.

(RSPCA Annual Report 1936)

It soon became evident how vitally needed the service was when requests for its assistance rocketed from 334 emergency night calls in its first year to 14,500 telephone calls and 2,552 emergency ambulance journeys in 1952 and then to 23,759 telephone calls, 1,411 ambulance journeys, 161 major rescues and 2,982 night clinic treatments in its late 1960’s heydays. Taking into context the small size of this unit, this was quite a major achievement.

Night Service proves popular & moves to Jermyn Street

After the second world war it operated from the basement of the old RSPCA Headquarters at 105 Jermyn Street, Piccadilly where it became known as the RSPCA London Night Emergency Service or NES as many called it. The old headquarters was a huge building on several floors, with a wonderful old staircase and a rickety Victorian lift. During the working day, a concierge resplendent in uniform and peaked cap stood on the steps at the front entrance to usher visitors in. When the staff vacated their offices in the evening, and the huge front doors were closed and locked, it seemed as though the famous RSPCA was dormant for the night, but at 5.30 pm the main telephone lines were transferred to an office in the basement and every weekday night and throughout the weekend, a small unit took over the reins of the world’s largest animal welfare organisation.

It had a small core of six dedicated staff divided into two shifts, who worked extremely long hours in basic conditions, which would be illegal today. The weekend shift was a long haul of 44 hours from midday on the Saturday through to Monday morning and the weekday shift from 5 p.m. to 8.30 a.m. averaging a 60-hour week. Luckily, it was possible for the two overnight staff to sleep when the calls upon their services diminished in the early hours while their third colleague was able to leave at 10 p.m. when the night clinic finished.

They had two heavy Austin Cambridge vans with the gear shift on the steering column which made them cumbersome to drive, but this did not stop the guys from driving at hair raising speeds through the then empty streets of London at night. They also had a large horsebox which was kept nearby in the Royal Mews with special permission.

They often put themselves at great risk in this Health and Safety free era to rescue animals from every predicament imaginable: “its’ officers were willing to have a go at anything“:

“Since it was inaugurated, the Night Service has become an important and essential feature of the Society’s work, justifying the boast that the RSPCA is on duty day and night. On a number of occasions members of its staff took great risks to rescue animals under hazardous conditions, climbing derelict buildings, wading through fetid sewers and balancing between electric railway lines”.

(RSPCA Annual Report 1960)

Apple Tree yard was well known in those days

The entrance to the night service was an unobtrusive door halfway down an uninviting dark cul-de-sac alleyway named Apple Tree Yard opposite the Red Lion Pub in Duke of York Street. The pub was a haunt of the night staff and duty vet and anyone visiting once the evening clinic had finished being only a matter of yards away. The alleway is unrecognisable today as all the original buildings on both sides have been demolished. There was no neon sign over the door just a dull light, but the service was so well known by every London cabbie, Police officer and Londoner it did not need advertising

You entered by walking down three steps and along a short, badly lit corridor turning right into a shabby waiting room, lined with plastic chairs and smelling strongly of disinfectant. To the left was an examination room containing basic equipment as these were the days before modern drugs and high-tech veterinary machines. Behind this room was a small recovery area with cages for the animals to get over the shock of whatever trauma they had suffered. There was no reception desk here, but a bell on the wall beside a door on the right which led to the inner sanctum. When you pressed the bell a door would open and dependent on the time of night and which part of the 60-hour shift you had arrived you were often greeted by a very dishevelled and bleary-eyed man, (no women allowed in those days!).

The telephones rang constantly until the early hours.

The inner sanctum was a large room some twenty feet square. Being mainly beneath ground level there was little natural light and the room had a dingy but restful feel by day or night. In fact, it was often difficult to know whether it was day or night until you went outside. On one wall was a large map of Greater London where an address could be pinpointed. Along another wall were six staff lockers and in a corner a kitchenette with the sink piled high with an assortment of cracked and grubby mugs, which supplied the much-needed caffeine. Scattered around the room were an array of easy chairs in various states of dilapidation and comfort. In a further corner, there was a bunk bed, beside it a large desk with three telephones. This was the most important part of the room and the person answering these emergency lines had the responsibility, through their guile, knowledge and inventiveness, for the health and welfare of hundreds of animals in the city. Each night they would ring constantly until the early hours.

I first came across the Night Service in 1970 when as an 18 year old newbie to both London and the RSPCA I discovered that because of its situation the unit was a meeting place or drop in for many staff visiting the West End which soon included me. The night room had a cosy and convivial atmosphere and was almost like a club with lots of banter and laughter. Its officers were willing to have a go at rescuing animals from every predicament imaginable, varying from the bizarre to the tragic and dangerous. I often listened to the many oft repeated old stories of past derring-do which were always greeted with much laughter.

Rescuing a naked woman trapped by a snake in her bath

There was talk of a terrapin rescued from the jaws of a crocodile that was kept in an ornamental pond in the foyer of a Mayfair Night Club, a pig rescued from an open well in the heart of London, a naked woman trapped in her bath for hours by a snake, an officer letting himself down by rope from the Highgate viaduct to rescue a pigeon and a turkey found wondering down a main road in Southwark, without visible means of support. Most stories were highly embellished but had a basis of truth especially one involving a night staff officer named Mike Chester who dangled on a rope under Charing Cross Railway Bridge, twenty metres above the tidal waters of the Thames to rescue a trapped pigeon. He was awarded the RSPCA Bronze medal for gallantry for this feat. All these tales and antics, often exaggerated, gave the Night Staff an almost mythical status

It was not all fun as I also gained so much valuable knowledge for the future by listening to these experienced doyens of the RSPCA answering the telephone to anxious and panicking pet owners. One was Harry Hunt who had been on the Society for some 35 years and had an amazing deep authoritative voice. He had a habit of calling everyone ‘my dear’: “Sounds very much like a burst abscess to me, my dear. Bathe it with warm salt water and keep the wound open. Get it along to your vet in the morning my dear. It will be alright“. Another was Nick Carter who was also a font of knowledge on animals and he appeared to survive on strong tea and toast, which he would not eat unless it was cremated. He would tip an old electric fire on its back and lay slices of bread over the grill, watching and turning them while he gave advice.

I was initially both entranced and puzzled at their advice, which often sounded like a witch’s brew. There was mention of Friars Balsam, Fullers Earth, China Clay, Bicarbonate of Soda and Epsom Salts to name a few, items which pet owners at the time, might have in their cupboards, which they could use for emergency first aid on their pet.

Tinned dog food and curry.

The night staff usually came prepared to cook for themselves as this was before the 24 hour society we have now and takeaways were few and far between. There was an all night cafe in Fleet Street, a food van in Parliament Square and the odd cafe in the markets such as Spitalfields or Covent Garden, but little else.

One of the more eccentric members was Vic Taylor, who loved reptiles and sometimes had one or two secreted on his person. He had a huge beard and a David Bellamy character and was often chef for the shift and wasn’t averse to cooking up some strange meals. There was a classic evening when he was asked what a strange tasting meal was and replied: : ‘Tinned dog food with loads of curry powder, supplies are a bit short I’m afraid.’

The RSPCA did not employ many of its own vets, so private vets from Central London often worked the one-hour evening emergency clinics at 9 p.m. Many of these in the late sixties and early seventies were characters and celebrities in their own right. One was Frank Manolson MRCVS well known for writing many pet care books including D is for Dog and C is for Cat. There was also John Newcombe, later a professor and an equine expert.

The Jermyn Street headquarters was allegedly haunted.

The old building at night was an eerie and frightening place and one duty the staff undertook was to wander the maze of corridors and offices over the six floors to check that all lights were off and all was safe. There was a maze of staircases and corridors winding their way through it. The building smelled incredibly old and reeked of polished wood and dust with background creaks and groans after a hundred years of use. In the middle there was a ground to rooftop well, allowing light to penetrate the centre offices of the building and this was traversed four floors up by an iron bridge with a drop to the basement.

There was a story often told that an RSPCA Inspector had committed suicide on this bridge by shooting himself with a humane pistol designed to shoot horses. It was believed that his ghost still stalked the bridge and corridors at night making it a spooky and frightening experience when you traversing the iron bridge.

Owners continued to arrive at the back door months after it’s closure – such was its popularity.

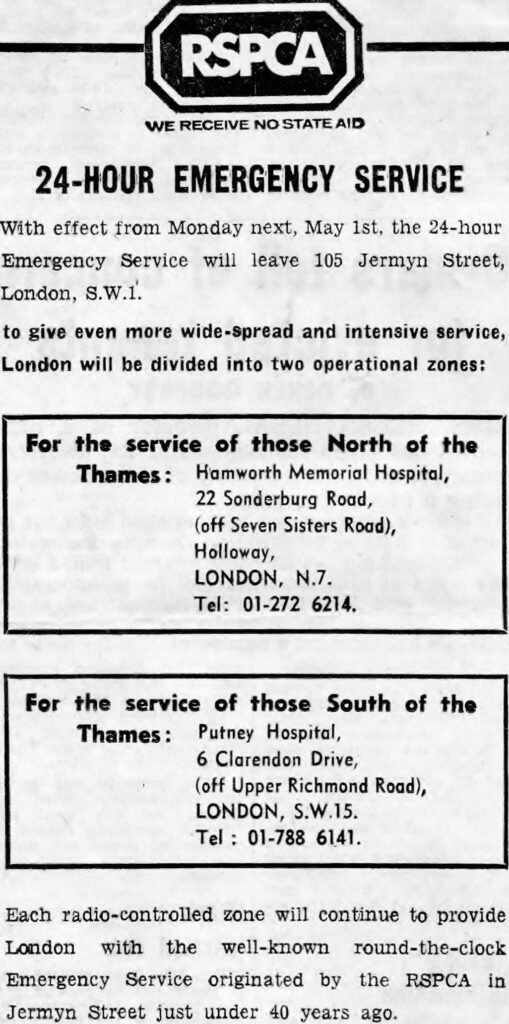

In 1972 the Society decided to move from Jermyn Street to larger and brighter offices in the countryside of West Sussex, so after 103 years of service the headquarters was to close. Staff and public were shocked at the announcement, as it seemed inconceivable that this wonderful building, which had seen so much history, could be demolished. With the headquarters closing, the fate of the NES and its 36 years of dedicated service was in the balance. There was considerable public outcry and representations were made to try to keep it working from the basement, or somewhere nearby, but to no avail.

Eventually it was decided to resurrect it in a slightly different guise, by dividing it between two hospitals that the RSPCA operated in London. Notices were placed in the London evening newspapers to inform everyone that Apple Tree Yard was no longer going to be the home of NES, but such had been its impact that for months afterwards, pet owners still arrived unannounced at the back door, clutching their sick or injured pets. A member of staff led a lonely and solitary existence there for three months redirecting people to the hospitals.

Times change and a sudden end to an incredible service.

It was a sad end to an incredible service, but times had changed and the calls for its assistance were decreasing. Vets were providing a better out of hours service and agencies like the fire brigade, police and other animal charities began providing more help. Half of the night staff decided not to move as they felt it just wouldn’t be the same free atmosphere and I took the opportunity to join paired up with the doyen Harry Hunt at the hospital in north London. The service limped on for a few more years, but the staff who had left were right; it wasn’t the same and the service was eventually absorbed and ceased to be a separate entity a few years later.

I had been lucky in spending many happy hours in the company of these good humoured, gung-ho and dedicated staff who seemed to thoroughly enjoy their work despite the hours and hardships. They had made it such a cosy, convivial and welcoming atmosphere and it was a shame it all had to come to an end.

Although the Service helped thousands of animals and pet owners during its 40 year existence it is now virtually forgotten except by the few of us still alive who had the pleasure of being involved and even the RSPCA archive has only a few vague references. It is a small piece of London and RSPCA history which needs remembering.

Some of the night staff who passed through the back door:

Officers: Pete Barton, Gordon Barker, Nick Carter, Mike Chester, Bruce Dakowski, Harry Hunt, Clive Pretty, Ray Richardson, Frank Salmon, Tony Sillars, Vic Taylor, Paul Thoroughgood, Veterinarians: Frank Manolson, John Newcome, Dave Presland, Glenys Roberts, Frank Wilson.