A lifeline for the city’s pets for 40 years.

The RSPCA London Night Emergency Service came in to being because 1930’s London was a far different place to that of today in respect to the number of animals residing within the Greater London area and the standard of animal welfare. Estimates suggest that there were 1.5 million cats, 400,000 dogs, 18,000 horses and a multitude of livestock including pigs and sheep.

Many Londoners still lived in real poverty, not the perceived poverty of today and most dogs and cats were left to the wander the streets and mingle with the large numbers of strays. Disease was rife and many suffered injuries particularly in road accidents. Few veterinary surgeries existed and even fewer animal rescue organisations with out of hours services. There were no council animal wardens and the police and fire brigade had little interest, ability or equipment to deal with animal related incidents. So, there was an opening for a service to fill all these gaps.

The London Night Emergency Service arrives.

It was therefore timely when in 1936 a new London emergency service quietly appeared on the scene which soon became a lifeline for worried pet owners, and the city’s sick, injured or trapped stray and wild animals within a ten mile radius of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) headquarters at 105 Jermyn Street, Piccadilly.

Over the next forty years its small dedicated staff were in great demand by the London Fire Brigade, Metropolitan, Transport and River Police, London Transport, and many other agencies and it rapidly became a true fourth emergency service in London at night and weekends.

Saving animals at the Crystal Palace fire

It got off to an auspicious start, when at about 9 p.m. on the night of the 30th. November 1936, it attended the great Crystal Palace fire at the request of the London Fire Brigade. Working alongside 700 Police officers, 438 Firemen and 88 fire tenders, its staff of two and one van helped rescue and attend to animals involved in the fire. According to an RSPCA report of the incident they arrived:

“With an ambulance fully equipped for first aid treatment, reached the scene in record time, and earned the grateful thanks of both Fire Brigade and Police”. (RSPCA Annual Report 1936)

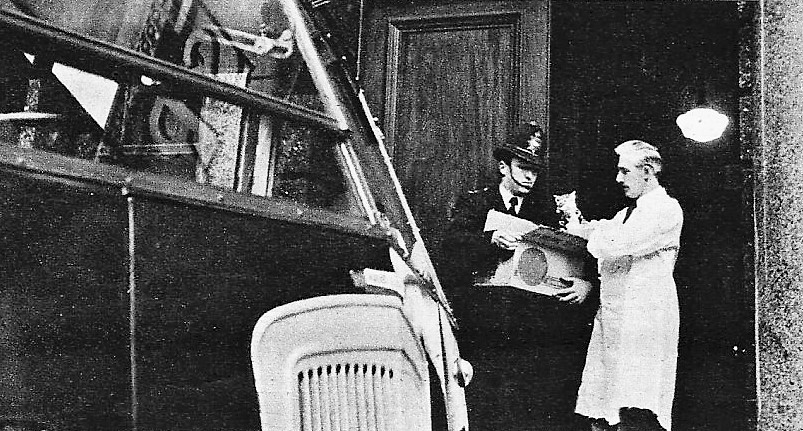

Initially housed at an RSPCA hospital in a converted house in Clarendon Drive, Putney, and known as the “Night Clinic,” it soon moved to the basement of their headquarters in Jermyn Street. It was eventually called the London Night Emergency Service (NES). Every London cabbie, police officer and Londoner knew of its existence and its location. It was arguably the first combined out of hours veterinary and animal rescue service and way ahead of its time operating a rapid response collection vehicle, equipped to carry out specialised animal rescues.

The Night Service takes off

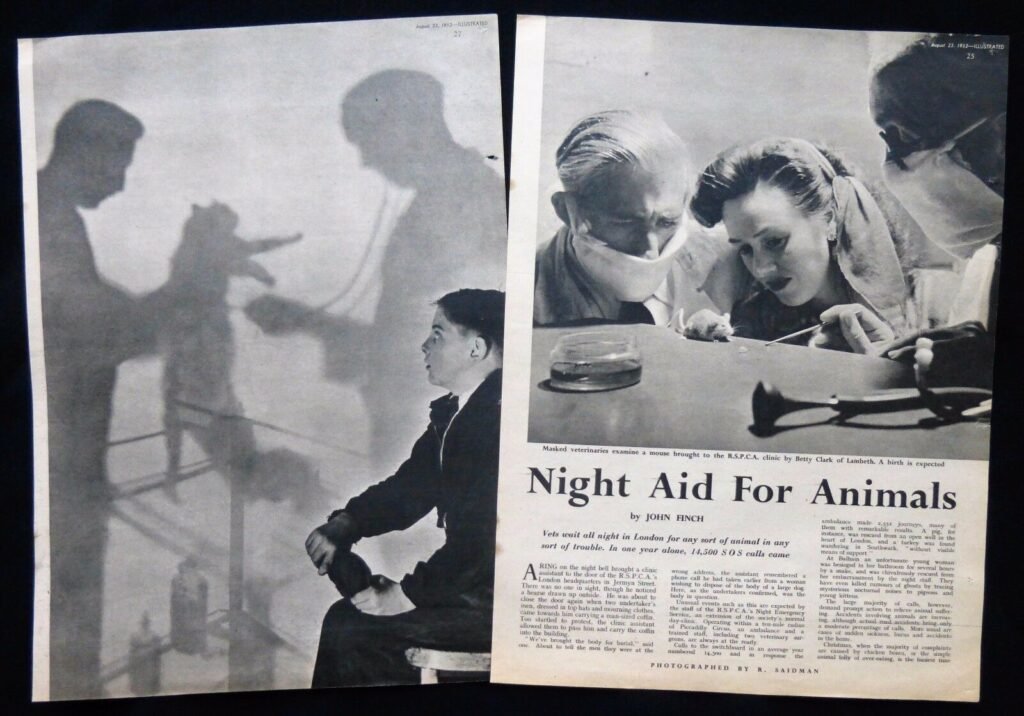

It soon became evident how vitally needed the service was when requests for its assistance rocketed from 334 emergency night calls in its first year to 14,500 telephone calls and 2,552 emergency ambulance journeys in 1952 and then to 23,759 telephone calls, 1,411 ambulance journeys, 161 major rescues and 2,982 night clinic treatments in its late 1960’s heydays. Taking into context the small size of this unit, this was quite a major achievement.

It was manned by six staff divided into two shifts, who worked extremely long hours in basic conditions, which would be illegal today, often putting themselves at great risk in the Health and Safety free era of the time, or as the RSPCA reported:

“Since it was inaugurated, the Night Service has become an important and essential feature of the Society’s work, justifying the boast that the RSPCA is on duty day and night. On a number of occasions members of its staff took great risks to rescue animals under hazardous conditions, climbing derelict buildings, wading through fetid sewers and balancing between electric railway lines”. (RSPCA Annual Report 1960)

The telephones rang constantly until the early hours.

The entrance to the night service was an unobtrusive door halfway down an uninviting dark cul-de-sac alleyway named Apple tree yard opposite the Red Lion Pub in Duke of York Street. It is unrecognisable today as all the original buildings on both sides have been demolished.

There was no neon sign over the door just a dull light and you entered by walking down three steps and along a short, badly lit corridor into a shabby waiting room, lined with plastic chairs and smelling strongly of disinfectant. To the left was an examination room containing basic equipment as these were the days before modern drugs and high-tech veterinary machines. Behind this room was a small recovery area with cages for the animals to get over the shock of whatever trauma they had suffered.

The night staff inner sanctum.

There was no reception desk, but a bell to summon help on the wall next to a door which led to the staff only inner sanctum. It was a large room some twenty feet square, mainly beneath ground level so there was never much natural light and it was often difficult to know whether it was day or night until you went outside. On one wall was a large map of Greater London where an address could be pinpointed.

Along another wall were six staff lockers and in a corner a kitchenette with the sink piled high with an assortment of cracked and grubby mugs, which supplied the much-needed caffeine. Scattered around the room were an array of easy chairs in various states of dilapidation and comfort. In a further corner, there was a bunk bed, beside it a large desk with three telephones which rang constantly until the early hours and a two way radio to the emergency ambulance.

They had two heavy Austin Cambridge vans with the gear shift on the steering column which made them cumbersome to drive, but this did not stop the guys from driving at hair raising speeds through the then empty streets of London at night. They also had a large horsebox which was kept nearby in the Royal Mews with special permission.

First aid advice sounded like a witch’s brew.

I first came across the Night Service in 1970 as an 18 year old newbie to both London and the RSPCA. I discovered that because of its situation the unit was a meeting place or drop in for many staff visiting the West End for an evening out which soon included me.

On my visits the telephones were usually being answered by two of the doyens of the RSPCA at the time. One was Harry Hunt with 35 years on the Society and the other Nick Carter. They used their vast knowledge and inventiveness to offer advice and reassure worried owners giving first aid advice or offering appointments to the night clinic. I would sit and listen, trying to absorb all the information they gave for future reference. The first aid they advised often sounded like a witch’s brew. Friars Balsam, Fullers Earth, China Clay, Bicarbonate of Soda and Epsom Salts, were all mentioned which pet owners at the time, might have in their cupboards and could use for emergency first aid.

A terrapin rescued from the jaws of a crocodile

Its’ officers were willing to have a go at rescuing animals from every predicament imaginable, varying from the bizarre to the tragic and dangerous. I often listened to the many oft repeated old stories of past derring-do which were always greeted with much laughter.

There was talk of a terrapin rescued from the jaws of a crocodile that was kept in an ornamental pond in the foyer of a Mayfair Night Club and a pig rescued from an open well in the heart of London. Also a naked woman trapped in her bath for hours by a snake and an officer letting himself down by rope from the Highgate viaduct to rescue a pigeon. On one occasion a turkey found wandering down a main road in Southwark, without visible means of support.

Although often embellished and exaggerated the stories all had a basis of truth. This was true of a night staff officer named Mike Chester who in 1960 dangled on a rope under Charing Cross Railway Bridge, twenty metres above the tidal waters of the Thames to rescue a trapped pigeon. He was awarded the RSPCA Bronze medal for gallantry for this feat (or perhaps it was madness).

Tinned dog food and curry.

The weekend shift was a long haul of 44 hours from midday on the Saturday through to Monday morning without a recognised break. Weekdays the shift stretched worked from 5 p.m. to 8.30 a.m. averaging a 60-hour week. Luckily, it was possible for the two overnight staff to sleep when the calls upon their services diminished in the early hours. The third colleague was able to leave at 10 p.m. when the night clinic finished.

They usually came prepared to cook for themselves. This was a time before the 24 hour society we have now and takeaways were few and far between. I remember a classic weekend night when the cook for the evening was asked what a strange tasting meal was and he replied: ‘Tinned dog food with loads of curry powder, supplies are a bit short I’m afraid.’

I spent many happy hours in the company of these good humoured and dedicated staff. They thoroughly enjoyed their work despite the hours and hardships. They made it such a cosy, convivial and welcoming atmosphere and it was a shame it soon had to come to an end.

Owners continued to arrive at the back door months after it’s closure – such was its popularity.

In 1973 the Society decided to move its headquarters to West Sussex and the fate of the NES and its 36 years of dedicated service was in the balance. The staff were obviously very upset about the decision and there was considerable public outcry. Representations were made to try to keep it working from the basement, or somewhere nearby, but to no avail.

Eventually it was divided between their two hospitals in London. Notices were placed in the London evening newspapers to inform everyone, but its impact had been so great, that for months afterwards, pet owners still arrived unannounced at the back door of Jermyn Street, clutching their sick or injured pets. A member of staff led a lonely and solitary existence there for three months redirecting people to the hospitals. Half the staff decided not to move as they felt it just wouldn’t be the same which gave me an opportunity to join the ranks.

Times change resulting in a sad end.

It was a sad end to an incredible service, but times had changed and the calls for its assistance were decreasing. New laws were reducing the number of stray animals, vets were providing a better out of hours service and other agencies and animal charities like the fire brigade and local authorities began providing more help. I transferred to the night service and paired up with the doyen Harry Hunt and it continued for a few more years until it was eventually absorbed and ceased to be a separate entity, but the old staff were right, it was never the same free going atmosphere.

Although the Service helped thousands of animals and pet owners and did incredible work, during its 40 year existence it is now virtually forgotten except by the few of us still alive who had the pleasure of being involved and even the RSPCA archive has only a few vague references. It is a small piece of London history which needs remembering.

Some night staff who passed through the back door of Jermyn Street:

Officers: Gordon Barker, Pete Barton, John Brookland, Nick Carter, Mike Chester, Bruce Dakowski, Harry Hunt, Bob Lambert, Clive Pretty, Ray Richardson, Frank Salmon, Tony Sillars, Vic Taylor, Paul Thoroughgood. Veterinarians: Frank Manolson, John Newcome, Dave Presland, Glenys Roberts, Tony Self, Frank Wilson.

Find Out How the Night Service operated, meet the people who worked for it and join them on dozens of bizarre and exciting rescues on the streets of 1970s London in this book:

ISBN:978-1479230419 254 pages with b&w photos.

Find out more on bitzabooks.com

RRP £6.99

Buy now using PayPal.

Special Offer £5.99 + £1.50 p&p

Also available on Amazon Books

Hi John

I have a memory of working there. It was on a Saturday, as you know, a straight 43hour tour of duty. I was designated the ambulance driver working with Pete Barton and Clive Pretty; and we received a call from the Station Sergeant at Notting hill Police Station to say they were attending an incident of a colourful striped snake in a tree which was getting agitated and he had given instructions to the constable on scene to destroy the animal rather than allow it to escape. I arrived on the scene before it had decided to move on.

I was in touch with the others via a two-way radio system and during the course of the journey, using the little knowledge Pete had obtained from the original caller, and Clive thumbing through our reference books (No internet in those days) we concluded that the snake was a harmless milksnake from America which was fast becoming a must-have pet in London.

Still, having a healthy respect for any wild animal out of its comfort zone that has the ability to bite, I decided that discretion was the better part of valour and using a thick black plastic bag which we kept on the ambulance, I gingerly placed it near to the animal and, using the seek and search (a powerful touch that was also part of the equipment we carried) I shone the bright beam into the snakes eyes. It immediately slid into the bag which I then carefully placed into a steel and glass cage in the van.

I then drove to London Zoo and the herpetologist took it to the reptile house and emptied into an empty clean vivarium. As it emerged the keeper literally jumped for joy.

“That’s not a milksnake” he said “It’s a coral snake and we haven’t got one. Thanks”. As an afterthought he said, “You weren’t bitten, were you?”. “No”, I replied. “Good” said the keeper, “‘cause these things are deadly”.

Just another routine day at the office! I don’t think I stopped shaking till I got back to Jermyn Street.